IMMANENTIZING THE ESCHATON, OR, WHATEVER IT IS, IT'S NOT 'CHRISTIAN'The Washington Post seems practically giddy over Brian McLaren and his 'new'

spin on Christianity. Why? Well because it 'challenges tradition', of course, and we all know that 'tradition' is bad.

But McLaren isn't really interested in Christianity or Christ in any meaningful way. Like a hip-hop artist he's sampling a few things from the New Testament for his own riff:

McLaren has emerged as one of the most prominent voices in an increasingly active group of progressive evangelicals who are challenging the theological orthodoxy and political dominance of the religious right. He also is an intellectual guru of "emerging church," a grass-roots movement among young evangelicals exploring new models of living out their Christian faith....

McLaren, 50, offers an evangelical vision that emphasizes tolerance and social justice. He contends that people can follow Jesus's way without becoming Christian. In the latest of his eight books, "The Secret Message of Jesus," which has sold 55,000 copies since its April release, he argues that Christians should be more concerned about creating a just "Kingdom of God" on earth than about getting into heaven.

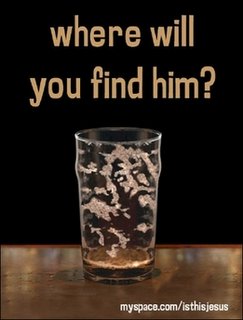

There is nothing more insidious than Christianity without Christ (or is that Christ without Christianity?) and salvation without heaven. This is nothing more than Eric Voegelin's definition of liberalism, 'immanentizing the eschaton', that is trying to make heaven on earth. To be somewhat more charitable, it is the old nineteenth century post-millennial approach, which sought to establish a perfect society--the Millennium--in order to hasten the return of Christ. Of course, these people aren't really interested in Christ returning. Christ is only relevant as a selectively edited starting point for their preconceived notions of social justice.

The central message of the New Testament is the redeeming death and life-giving resurrection of Jesus. Jesus said many vitally important things, but those teachings are relevant only if Jesus died and was raised again. In other words, the teachings of Jesus are only critical insofar as they are linked to salvation and resurrection. If you sever that tie, then Jesus is not a good teacher, he was a liar or madman.

McLaren has tapped in to some real discontent. As the article points out, the often superficial appeal of the megachurch movement left many understandably cold. The popular idea of the evangelical 'patriotic Jesus' clearly has gone much too far, which McLaren twists to slide in his leftist talking points:

"When we present Jesus as a pro-war, anti-poor, anti-homosexual, anti-environment, pro-nuclear weapons authority figure draped in an American flag, I think we are making a travesty of the portrait of Jesus we find in the gospels," McLaren said in a recent interview.

And the facile and unscriptural--yet ubiquitous--'Sinner's Prayer', which throws aside the commitment of taking up one's cross and following Jesus in exchange for a feel good moment has left a gaping hole for those who really see a need for acting out their faith:

"The modern Christian formula of 'I mentally assent to the fact that Jesus died for my sins and therefore I get to live forever in heaven' . . . is entirely cognitive," said Ken Archer, 33, a D.C. software entrepreneur who is studying philosophy at Catholic University. "It's a mathematical formula [that] leaves the rest of our being unfulfilled."

But the failings of the modern evangelical movement can't be solved by turning diversity, environmentalism and social justice into idols.

Building on such a foundation--a foundation that excludes the reality of Christ and His teachings--will not lead to anything other than causing some to substitute worldy goals for spiritual ones. The often quite sensible D.A. Carson likely is right in his assessment:

Though a "creative, sparkly writer," added Carson, McLaren has "got so many things wrong in his analysis that his work is not going to last that long."

Modern evangelical Christianity does have gaping holes in it, but McLaren's new take on the Benevolent Empire isn't the answer. Whenever we find Christianity wanting, it is never the fault of Christ--or of Christianity--but rather of those who claim to be practicing it. The answer always involves the often difficult task of assessing my own life and practice in the light of Christ on the cross, and His teachings and those of His apostles as recorded in the New Testament.